In the first of our new series, Revd. Canon Jonathan Baker looks at the account of the resurrection in St. Matthew's Gospel and Piero della Francesca's painting of the subject.

The Resurrection according to Matthew and Piero della Francesca

In this new series I am using the fact that we are still technically in the Easter season as an excuse to talk about the resurrection of Jesus. I want to do this by taking each of the four Gospels in turn to see what particular understandings Matthew, Mark, Luke and John each has to bring to this glorious central event of the Christian faith. And to help us to do that, each week I’m going to refer to a painting. The reason I’m going to do that is because artists, by the very nature of the case, have to look very carefully at their subject matter. They have to study it, to look closely at it, to pay attention and allow it to speak to them. In this way the artistic enterprise has some important parallels with prayer – they are both ways of listening in order to receive fresh insight. So where an artist has produced a great painting as a result of reflecting upon a passage of scripture, it’s almost as if we’re listening to a sermon – or at least a commentary – upon that text. So by involving a painting each week, I’m hoping to open up a three-way conversation between the Evangelist, the Artist and myself as the present day speaker, out of which I hope that something of God’s Word will be heard.

In this new series I am using the fact that we are still technically in the Easter season as an excuse to talk about the resurrection of Jesus. I want to do this by taking each of the four Gospels in turn to see what particular understandings Matthew, Mark, Luke and John each has to bring to this glorious central event of the Christian faith. And to help us to do that, each week I’m going to refer to a painting. The reason I’m going to do that is because artists, by the very nature of the case, have to look very carefully at their subject matter. They have to study it, to look closely at it, to pay attention and allow it to speak to them. In this way the artistic enterprise has some important parallels with prayer – they are both ways of listening in order to receive fresh insight. So where an artist has produced a great painting as a result of reflecting upon a passage of scripture, it’s almost as if we’re listening to a sermon – or at least a commentary – upon that text. So by involving a painting each week, I’m hoping to open up a three-way conversation between the Evangelist, the Artist and myself as the present day speaker, out of which I hope that something of God’s Word will be heard.

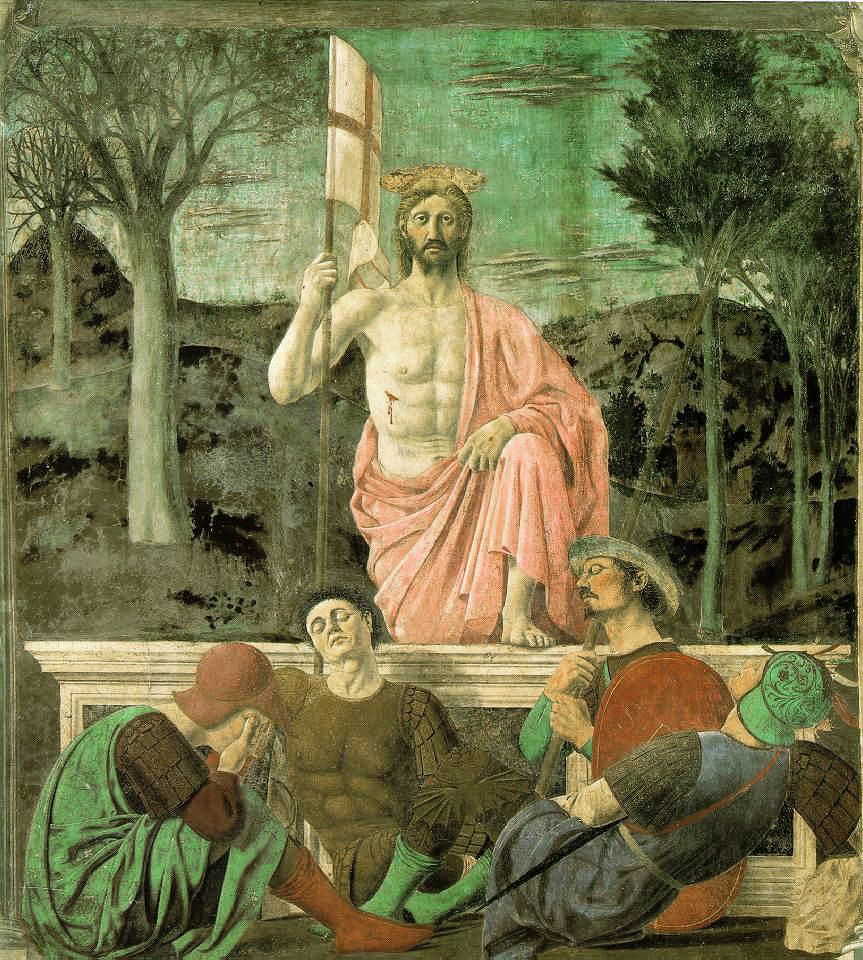

So we start with St Matthew. The painting I’ve chosen to illustrate Matthew’s account of the resurrection was painted in the early 1460s by the great Italian renaissance master, Piero della Francesca. And it’s a masterpiece. The great art critic Kenneth Clarke described it as ‘one of the supreme works of painting.’ The novelist Aldous Huxley, who wasn’t a Christian, described it as simply ‘the greatest picture in the world’ – which is quite a claim.

But I have to acknowledge straight away that this amazing painting does not correspond exactly with Matthew’s account of the resurrection – or indeed with any of the gospel accounts. Because none of the Evangelists presumes to describe the moment of the resurrection itself. The two features of Matthew’s account of Jesus’ resurrection are, firstly, the women meeting an angel and being shown Jesus’ empty tomb; and then, secondly, their meeting with the risen Lord who comes to them and greets them. But the moment of resurrection has already taken place before the women appear on the scene. It’s an event full of mystery, unobserved, taking place in silence. The disciples are witnesses of its aftermath, not the event itself. But Piero della Francesca is bold enough to show us the exact moment of resurrection, as Jesus climbs triumphantly out of the tomb. In one sense the artist isn’t doing anything particularly novel here; there was a tradition of medieval iconography going back centuries which depicts this moment in stylised form – we can see it in stained glass, in monumental brasses, in illuminated manuscripts, where Christ is shown standing up from a table tomb surrounded by sleeping soldiers. But Piero della Francesca shows it better than anyone else. If you think about it, showing the moment of the resurrection is a huge challenge – how do you depict such a moment without being kitsch? How do you present a unique moment of divine intervention, the decisive event in all the cosmos, when the power of God destroys the power of death? How do you do that without special effects – without hosts of angels, or special lighting effects, or symbols of heaven and eternity? And how do you show it without compromising Jesus’ humanity – making it clear that this is a real human being with whom we can all identify, as well as the unique Son of God?

Somehow Piero della Francesca achieves this. His Jesus dominates the scene, standing centrally in the composition. The original painting is a fresco, 7 feet high, on the wall of the Town Hall in San Sepulchro, Italy – so it is life-size. His upright, vertical figure stands in contrast with the horizontal lines of the tomb, the horizon, and the heads of the sleeping guards beneath him, which emphasises the resurrection theme and divinity of Jesus. Yet the figure of Jesus is completely human. The artist is a true representative of the Renaissance, which rediscovered the beauty and glory of the human body. And Jesus is beautiful without being idealised. His stomach is wrinkled where his leg is raised. His beard is scratchy and unimpressive. And his humanity is emphasised by the fact that the wound in his side is still bleeding. His eyes have no pupils. They are dark pods into which we can project our own meaning. Is Jesus’ gaze dazed, as one waking from sleep? Or is it confident, challenging us to disbelieve what is happening? Certainly his gaze fixes us, draws us in, and invites a personal encounter. More on that later.

The divinity of Jesus is evident most obviously in the halo above his head, and in all the symbolism of triumph – the foot confidently placed on the edge of the tomb, as if trampling down death itself. The vertical banner touching the upper edge of the picture – the banner which symbolises triumph and victory, and for that reason came to be associated with a number of Christian saints, especially St George, and which also commended itself to Edward III who adopted it as the badge of the Order of the Garter and thence as the English flag. So when you see the cross of St George you shouldn’t be thinking of the British National Party, you should be thinking of the victory of the resurrection.

The divinity of Jesus is suggested not just by his centrality and imposing posture in the picture. Piero della Francesca was a master of geometry and of perspective. And in this picture there are two different perspectives, not one as you would expect. On the one hand, the viewer stands below Christ. We can’t see the top of the tomb. The necks of the two central guards are foreshortened, as if we are looking up at them slightly. On the other hand, Jesus doesn’t look down on us but straight at us as if we are on the same level as his eyes. This has the effect of putting the figure of Jesus on a different plane from the rest of the picture, suggesting his divine nature, whilst at the same time drawing us closer to him, as if we are being invited by the intimacy of his gaze to draw near.

And then there is that pink cloak. Pink is the colour of joy and happiness, which seems perfectly appropriate. It is also the colour which in medieval Christianity symbolised marriage. So what the artist is perhaps suggesting here is the spiritual marriage of heaven and earth, the marriage of Christ and his Bride on earth, the coming together of the human and the divine, the Church, the marriage of the old creation and the new – notice in the background the contrast between the dead trees of winter on the left and the green leaves of spring on the trees on the right and it’s as if the resurrection is not just about Jesus – through him all the world is being made new. The resurrection is the great divine act of transgression, breaking the boundaries of sin and death and earth and time, and allowing forgiveness and grace and new life and heaven and eternity to flood in. All of that is suggested by the pink robe, and echoed by the renewal of all creation in the background.

The reason I’ve chosen this picture to go with Matthew’s account of the resurrection, even though Matthew doesn’t describe this particular moment, and even though this artist doesn’t show either the angel or the women who feature in Matthew’s Gospel, is because it seems to me that what Matthew and Piero della Francesca both share is a supreme confidence in the reality of this event. In Mark’s Gospel we have the empty tomb, a mysterious young man in white, and the women running away afraid. In Luke we have angels and terrified women whose story isn’t believed by the apostles, and we have disciples on the road to Emmaus who fail to recognise Jesus, and he has to come to them in the Upper Room and explain it all. In John we have the empty tomb and puzzled disciples, and then Mary mistaking Jesus for the gardener. But in Matthew, it’s all perfectly clear and straightforward. And although he doesn’t describe Jesus emerging from the tomb, he comes closer than any of the other Evangelists, saying that as the two Marys went to the tomb at dawn, ‘Suddenly there was a great earthquake; for an angel of the Lord, descending from heaven, came and rolled back the stone and sat on it…and for fear of him the guards shook and became like dead men.’ So here we have the moment at which the tomb is opened, and we have the guards mentioned, who don’t feature in the other gospels – but we don’t quite see Jesus yet, and the angel suggests that Jesus had already been raised before the stone was rolled away. In the Gospels, of course, the tomb is cut into rock, whereas for Piero della Francesca it’s a classical table tomb of 15th century renaissance, so there is no stone to roll away.

But despite all these differences, l there is a clear moment of encounter. Just as the women are leaving the tomb ‘with fear and great joy.’ ‘Suddenly, Jesus met them and said “Greetings!” And they came to him, took hold of his feet, and worshipped him.’ There is no ambiguity about this, there is no doubt or uncertainty. Jesus is risen, he greets them triumphantly, they know who it is, and they respond with worship and adoration. That’s what this picture communicates. The artist, like Matthew, is supremely confident that this is something that really happened, and he wants to convince of this, and to persuade us that this is the most real thing that ever happened. Matthew the tax collector knew what it was to meet Jesus and to have his life turned around by Jesus. His gospel is in one sense a personal testimony written so that others may believe. Piero also paints as a personal witness. There is a tradition going back to not long after Piero’s death that the sleeping soldier second from the left is a self-portrait. He includes himself as a representative of the sleeping world, unaware and indifferent to the risen Lord, as if inviting all of us to wake up and to see.

The painting does connect us with the resurrection in other ways too – as I said, it is a fresco which can be seen in the town of San Sepulchro – a name which means ‘Holy Sepulchre.’ It is so called because it was founded in the 10th century by monks who had brought shavings of The Cross from Jerusalem. So the whole community exists because of a tangible link with events of Christ’s passion, and the painting was commissioned to go in the Town Hall to reflect that connection. So, just as Matthew provides the link between his gospel and the events they describe, something similar might be claimed for the town of San Sepulchro – this painting is a crucial part of the town’s identity.

And the painting speaks almost as the gospel does. In World War II, as allies were driving German forces back up the spine of Italy, it was normal to bombard each town before sending in the ground forces. When they came to San Sepulchro, they began to do the same. But the British officer in charge of the artillery, Tony Clarke, thought the name San Sepulchro sounded familiar. And as the first few shells landed, he realised why he knew the name – it was because he had read Aldous Huxley’s 1925 essay which described San Sepulchro as the home of the greatest painting in the world. So in direct disobedience to his orders, Tony Clarke ordered the shelling to stop. Thankfully, the Germans had already left the town. So both the town and the painting were saved, and after the war, Tony Clarke was feted by the townspeople as a hero, and a street was named after him. Even though Tony Clarke had never actually seen the painting, his memory of its description saved the town from destruction.

So with us. Jesus in the Gospel meets us, as well as the women, and says ‘Greetings!’ and invites our response, of praise and worship and joy. In the picture you’ll see that it has an architectural frame, with pillars on either side, and a lintel. It’s as if Christ, having fixed us with that intimate, mesmerising gaze, is now going not only to step out of the tomb, but he’s going to step of the frame, out of 15th century renaissance Italy and into our world and our lives, inviting us to awake, to greet, to worship, and to be made new. The gospel and the painting were each made centuries ago. But they were both made to present the risen Lord to subsequent generations afresh. They are part of a confident expression of the victory of God, and they give us a glimpse of a world renewed. So as we gaze into the face of Jesus stepping from the tomb, so let us allow ourselves to be seen and known by him. Let us hear afresh his words of greeting and love and peace; and as we are moved to worship and adore, and to go and tell, let us become more mindful of the possibility that we ourselves might be masterpieces of the great Artist, in whose faces Christ may yet be seen, and in whose voices his Word can still be heard.